Jacob A. Waddingham Assistant Professor of Management, Texas State University

Miles Zachary Associate Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship, Auburn University

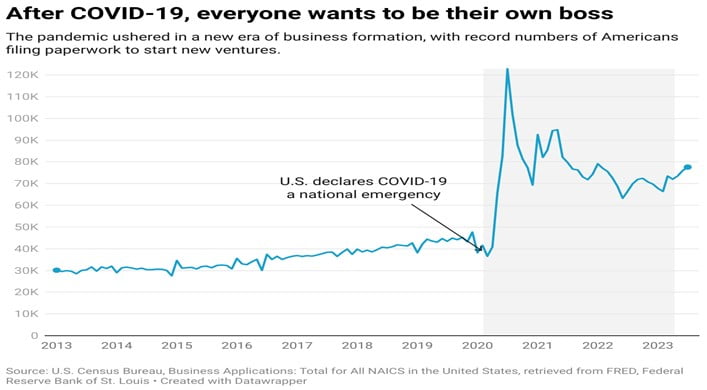

If you’ve been thinking about starting your own business lately, you’re not alone. Americans began launching ventures in record numbers during the pandemic, with an above-trend pace continuing through 2023.

Unfortunately, many of of these enterprises won’t last long: 30% of new businesses fail within two years, and half don’t last past five, according to the Small Business Administration. While some of these unlucky founders will pursue new ventures, many others will try to rejoin the traditional labor force.

You can’t blame them. People often see “going back to work” as a safety net for risk-taking entrepreneurs. As professors of management who study entrepreneurship, we wanted to see if this was true.

Screened out

So we surveyed more than 700 hiring professionals to determine whether founders really can get new jobs that easily, as well as seven former entrepreneurs who successfully made the transition back into the workforce.

We found that former business owners were actually less likely to get interviews compared with applicants with only traditional experience. This was true regardless of whether they had sold or closed their businesses. And the longer they were out of the traditional workforce, the worse their chances of success were.

Why do employers hesitate to take a chance on former business owners?

It starts at the earliest stages, with the recruiters who screen people into – or out of – consideration for interviews. We found that recruiters worried that entrepreneurs would jump ship to start their own companies as soon as they can. This is a problem for employers, since hiring is a long, expensive process that can take months or even years to pay off.

For example, one recruiter told us, “I am looking for candidates that will be long-term employees, as we invest quite a bit into each hire. When I interview people, it is generally a red flag if they say they want to start their own business or already have a business on the side.”

A related fear: A worker who leaves to start a new venture might be tempted to poach talent, clients and tactics from their old employer.

Recruiters were also concerned that former entrepreneurs may refuse to take directions. Spending time as your own boss can make it difficult to adapt to a lower place on the organizational hierarchy. As one recruiter in our study put it, former business owners “are used to being the one who makes all the decisions.”

They also raised issues of job fit, questioning whether ex-entrepreneurs’ knowledge and abilities would translate to traditional work. “The concern would be the skills they have developed don’t transfer,” said one of our interviewees. In addition, for entrepreneurs who have worked alone, it can be difficult for recruiters to know how well they’ll perform with others.

Even when a former entrepreneur is a good match for a position, recruiters can fail to make the connection because of stereotypes or misunderstandings about their experience. A former bakery owner we interviewed recalled applying for a position and being pigeonholed based on their experience: “They said, ‘Oh, I wish we were hiring for a baker!’ and I said, ‘No, no, no, I’m applying for your front office.’ It was like they thought all I knew was just a baker, but that is far from the truth.”

Landing an interview

Our research adds to a growing body of evidence that ex-entrepreneurs struggle to get interviews and offers. Thankfully, it also offers insights that organizations can use to improve their applicant pool – and that enterprising job seekers can use to boost their odds.

Our study found that former entrepreneurs face less bias when they apply to roles that seem entrepreneurish – in other words, that are in line with stereotypes about business owners. So, for example, they’re more likely to land interviews when applying for positions with a lot of autonomy, such as in new business development, rather than those that require following lots of rules, such as in legal compliance.

Relatedly, our research suggests that recruiters – perhaps unintentionally – have biases against ex-entrepreneurs. Acknowledging such tendencies is a good first step toward minimizing their influence. Moreover, not all recruiters are equally affected: Another recent study showed that recruiters who also have prior entrepreneurial experience – as well as women and those who were recently hired – were less likely to screen out former business owners. So organizations with more diverse hiring teams and a deeper understanding of entrepreneurial experience might see less-biased results.

For their part, ex-entrepreneur job applicants would be wise to highlight in-demand aspects of their work history. For instance, a recent survey by Boston Consulting Group found that executives rank innovation as one of their top three priorities. Former entrepreneurs should emphasize their many valuable characteristics – such as being passionate and creative – that contribute to innovation. The lack of a traditional employment history may create obstacles for entrepreneurs trying to rejoin the workforce. Recruiters who overlook their value risk missing out on strong candidates. (The Conversation)