This article was originally published in the July/August 2020 issue of The American Conservative. John A. Burtka IV is the executive director and acting editor of The American Conservative.

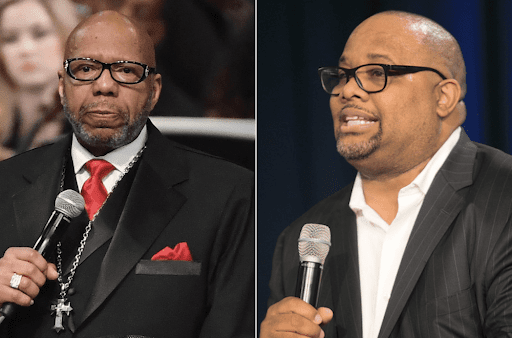

In the Middle Ages, they might have been called “fools for Christ.” The Sermon on the Mount assured that such men were storing up “treasures in heaven, where moth and rust do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal.” Equal part pastors, diplomats, and prophets, they are men of action who have turned the conventional narrative about race and poverty on its head in order to strengthen black America. Some might even call them saints.

Pastor Corey Brooks stood at the altar of New Beginnings Church on the South Side of Chicago. The sanctuary sits at 6620 S. King Drive, just south of “O-Block,” known as the most dangerous neighborhood in Chicago. It was the summer of 2011, and Brooks was tasked with burying yet another victim of gang violence—the city averages over 2,000 shootings per year. This time, Brooks had had enough.

As he surveyed the congregation, he decided to do something that many pastors do all the time, an altar call. But this time, instead of asking people to bend a knee, he sensed that some were carrying illegal firearms in the sanctuary. He pleaded with his congregation to lay down their weapons. The room fell silent. For a moment, he feared for his life. But then, the silence was broken when a young man came forward and placed his gun on the altar. After the memorial, he discovered several other guns left beneath the pews by men who had been too ashamed to stand up before the community, yet clearly wanted to amend their lives.

As he left the church, he looked down the street towards a motel whose presence weighed heavily upon the members of his congregation. The Super Motel was an epicenter for sex trafficking, drug use, and prostitution. For the past 18 months, he had led protests with over 100 people on Friday and Saturday evenings, calling on law enforcement to shut down the den of iniquity. Eventually, Chicago police heeded his request, but the abandoned property still attracted illicit behavior even after its closing.

That’s when Brooks felt another nudge on his heart similar to the one he felt at the funeral. The situation required action, and he felt that God was knocking on the door. He responded by taking to the rooftop of the motel in prayer and protest. For the next 94 days, during a blisteringly cold Chicago winter, Brooks camped out and refused to come down until he raised $450,000 to purchase and demolish the structure. His efforts attracted national attention, and he was successful in accomplishing his goal.

Fast forward to 2020: Brooks now oversees both his church and a vibrant community center on the site of the old motel, Project H.O.O.D., whose mission is to empower community members with the “tools necessary to become peacemakers, problem solvers, leaders, and entrepreneurs.” Serving over 2,000 people, his team has helped to launch countless start-ups, provide job training for certified construction workers, start a violence prevention and conflict mediation program, offer financial coaching to thousands, and countless other programs from summer camps to providing a safe place for teens to gather on Friday evenings.

O-Block is safer on account of his efforts, and he’s developed street cred with gang members who respect the investments he’s made in the community. When asked what drives his seemingly endless ambition, Brooks responded with two things: “I really believe in God and I really do believe that one day I’ll have to stand before him and give an account for my time on earth…And then secondly…I want people to see that you can be conservative, and you can be black, and you can be in the hood, and make these principles still work.”

Pastor Jasper Williams took the podium at Greater Grace Temple in Detroit and ignited a powder keg. It was August of 2018 and the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin, was being laid to rest. The marathon, eight-hour service was attended by an A-list of celebrities and politicians including Ariana Grande, Jennifer Hudson, Whoopi Goldberg, Stevie Wonder, Bill and Hillary Clinton, Eric Holder, Jesse Jackson, and Al Sharpton. They did not know what Williams had in store.

Williams was a longtime friend of the family, having eulogized Aretha’s father, Rev. C. L. Franklin, a civil rights leader and organizer for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. A family tradition, Williams was invited back to pay his respects to Aretha, which he did with aplomb. What they didn’t anticipate, however, was that he’d take the occasion—in front of a national audience—to issue a stirring wake up call to black America.

“Black America has lost its soul,” he declared. It was time for the community to “come back home to God.” Now Williams is an eloquent orator—and an even better singer—so he seasoned his fiery sermon with sweetness and fatherly affection to build support from his audience, at least up to the point when he revealed his core concerns.

There was a time, he said, when black Americans had their own booming economy. Segregation was a grave injustice and positive evil, yet it forced the community to depend on each other. Black Americans owned their own grocery stores, barber shops, banks, and hotels. The community was thick. While integration was the chief accomplishment of the civil rights movement, Williams lamented that it was accompanied by “the loss of the black economy and the loss of the black man’s soul.”

Williams went on to lament that there are no fathers left in black homes and no men around “to raise a black boy to be a black man.” A revival of the family, specifically the home, said Williams, would mean more to the black community than any house that “Big Government” or “Big Business” wants to give them. In one of his most celebrated and often repeated lines, he proclaimed, “As the home goes, so goes the street. As the street goes, so goes the neighborhood. As the neighborhood goes, so goes the city. As the city goes, so goes the county. As the county goes, so goes the state. As the state goes, so goes the nation. As the nation goes, so goes the world.”

At the pinnacle of his sermon, Williams pushed the boundaries further by grabbing another third rail of American politics: black-on-black crime. He lamented that nearly 6,000 black people are killed by each other every year, according to a study from the Tuskegee Institute. “Do black lives matter?” he asked. “No, black lives do not, will not, ought not, should not, must not matter until black people start respecting black lives.” We can hear Aretha’s voice speaking to us today, he concluded, “It’s time now that my race turns around and comes back to God.”

The backlash was fierce. “Aretha Franklin’s family slams pastor’s ‘very, very distasteful’ funeral eulogy” read a headline at USA Today. NBC wrote that he “stirs controversy.” NewsOne called his sermon “a disgrace.” And Essence said, “Many were not happy with the eulogy.” According to AP News, “Williams was blasted on social media for misogyny, bigotry and the perpetuation of false science on race.” Unflinching, Williams stood behind his remarks.

Were these the words of a madman or a prophet? Had Williams himself lost touch with the soul of black America? Outsiders might ponder these questions, but his actions tell a different story. Known as “a man with a heart for the people,” and “Son of Thunder” for his service to the local black community and magnetic preaching, Williams and his son pastor a congregation of approximately 10,000 people at two locations in Atlanta. When his flight got back from Detroit, Williams told me that he was heralded as a hero by his congregation.

If anyone is in touch with the needs of the black community, it’s Williams. Born in Memphis, Tennessee, he attended Morehouse College in Atlanta on account of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who would later become a friend and even solicit his advice on how to become a more effective preacher. For the past 70 years, Williams has been preaching and serving his community week in and week out.

In 2014, after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Williams said that “I heard the voice of God: Something needed to be done…and…[it] needed to be done through the church.” He considered protests and boycotts of white businesses, but after seeking the counsel of a close friend, he chose to call a meeting at the Commerce Club in Atlanta for civic leaders from every county in the metro area.

His goal was to “turn black America around.” After hearing from community leaders and conducting a listening tour during the next six months, he collected his data and met with Dr. Mary Langley at the Morehouse School of Medicine, who prepared a qualitative analysis of his findings. The results showed that the three greatest needs in the African-American community were family, home, and parenting.

Over the past six years, he’s developed a parenting curriculum that’s widely taught in churches and schools in the Atlanta area through his non-profit organization, A.A.C.T.S. (African-American Churches Transforming Society). Furthermore, his church also provides a wide range of services including welfare assistance programs, childcare, counseling, eldercare, and support for single-parent households.

If Williams emphasizes the reforms that can be made at the local level in African-American families, he also acknowledges the legacy of racism, and its impact on the black community. In his autobiography, It Ain’t But One, when discussing the issue of black-on-black crime—the lightning rod that sparked most of the criticism for his eulogy of Aretha Franklin—Williams cites “covert racism,” more than “overt racism” as the source of the problem. He explains that “the spirit of slavery still lingers” today. He notes that “white slave owners pitted their slaves against each other as a way of keeping them from uniting in opposition to slave holders.” This “atmosphere of suspicion,” he notes, “was a system of divide and conquer, and its terrible effect can be seen in our culture to this day.” Nevertheless, when looking for solutions to the grievances voiced by protest movements today, he believes that the most fruitful place to start is in the home.

What motivates Williams? Where does he get the courage to preach with such boldness as he did at Aretha’s funeral? “All you got to do is drive through our community and see how destitute our community is,” he said. He described the ethos as “lackadaisical,” “apathetic,” “nonchalant,” and lamented that there’s “no desire for true life.” Their pain is evident, and Williams understands it first hand. In the 1980s, Williams found himself addicted to cocaine while simultaneously trying to pastor his church. He hid his habit from the congregation, but his life began to spiral out of control. After battling with the addiction for years, he finally checked himself into rehab. He’s been clean ever since, and his testimony serves as a powerful example to those in his community struggling with the same issue. The situation on the ground is intolerable. “That’s drive enough for me,” he concluded.

There is a stigma in the black community against being conservative or Republican. Presidential candidate Joe Biden, who later apologized for his comments, provided the case in point when he recently stated: “If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t black.”

Pastor Corey Brooks is all too familiar with this presumptuous mindset. When he surprised his community by endorsing a Republican candidate, Bruce Rauner, for governor of Illinois in 2014, the costs were beyond anything he could have ever imagined. He received death threats and had to hire private security. His family had to go into hiding, and his church was broken into and burgled. Seventy-five percent of his 2,500-member congregation left (taking their tithes with them), and unions were bussed into his neighborhood to protest day after day.

While he was taken aback by the reaction, he can personally relate to their feelings. When he was a freshman in college, he recalled, a professor wrote a bunch of political positions on the board without any labels. Each student had to identify where they stood. He found the set of principles that most closely aligned with his values and waited for the professor to reveal the labels. He “almost fainted when he saw his views were conservative and Republican.” His family had always been liberal and Democrat. How could this be?

Pastor Jasper Williams, on the other hand, resists labels altogether. When I asked about his political affiliation during our video interview, he said that “I’m not a Democrat or a Republican,” and prefers to call himself a “theo-crat-con based on what God says about the issues.” He elaborated on this point by explaining his frustration with how both parties treat African Americans: “The Democrats take us for granted, and the Republicans don’t think enough of us to ask us.” While Williams eschews partisanship, there’s no question that his views about the family and personal responsibility align more closely with beliefs conventionally held by conservatives than by liberals.

When I pressed Brooks to define conservatism, he gave the following principles: “fiscal responsibility,” “less governmental involvement,” “family focused,” “entrepreneurship and free enterprise,” and “not need[ing] all these social programs…to succeed.” Brooks notes that “Blacks embody conservatism…we have conservative views and thoughts, but it doesn’t translate into our political party affiliation.” For example, the church is a recognized source of authority in black neighborhoods, even for those who do not attend services regularly. And the importance of family, and intergenerational bonds, is widely esteemed in their communities. In short, black conservatism is a way of life more than an ideology.

As I spoke with Brooks, I was curious about his thoughts on the ideological shifts that have taken place on the Right since Trump’s election in 2016. Many have talked about a conservative realignment on issues like the Iraq war, immigration, and globalization. Mitt Romney’s platform looked a lot different than Donald Trump’s. The party of hedge fund managers became the Republican Workers Party, or so many have claimed. Did he identify with one brand of conservatism more than the other?

Brooks told me that the “workingman’s message is more appealing…[but] Trump himself makes it hard for the message to be received.” Reflecting on the issue of globalization, he said that it became hard for families to take care of themselves when they lost the strong economic bases in their communities. He also noted that “a lot of African Americans do believe that…[on account of] being so loose with immigration…a lot of jobs that young African Americans could have, they’re not available.” He discussed the pervasive myth among American elites that “nobody wants those jobs anyway.” He rejects that notion emphatically, saying “that’s not true,” and personally knows many people who would do these types of jobs if they had the opportunity.

When I asked Williams about the shifts in conservatism, he was more measured. While he agreed with Brooks’s analysis about the economic impact of immigration, he thought that the GOP was “too harsh and hard on keeping people out,” and that we should encourage immigration provided it’s done legally. And he noted that, when it comes to healthcare, it seems like Republicans “don’t have a plan.” On foreign policy, however, he acknowledged that Trump may have been right to a degree: “we have been too involved in other nations’ business.”

Where did it all go wrong? Both pastors pointed to the period immediately following the civil rights era. Speaking of Martin Luther King Jr., Williams said, “You can’t judge a man out of his times. Martin Luther King contributed a lot to the aggrandizement of the African-American community. No question about that. But with us looking back, we have 20/20 vision.” The civil rights movement accomplished many good things; however, the loss of the black economy and black-owned business that followed had far reaching consequences.

Brooks points to liberal policy: “Government got too involved…in our families, and they started to fall apart.” He acknowledged that there are “underlying racial issues” that disparately affect blacks, “but even more so it’s about poverty.” He complained that all of America’s largest cities have the same issues affecting African Americans, and they are all run by Democrats: “High unemployment,” “high incarceration,” “lack of businesses,” “high single-parent households,” and “high abortion” rates.

He was very excited to see Republicans pick up the criminal justice reform issue, saying that it’s “real important…we have a lot of people who were incarcerated for way too much time for non-violent offenses.” He blames Clinton and Biden-era liberals for locking up a lot of men. “Hillary Clinton called them predators,” he said. Their policies “led to them [black men] being locked up more than anybody.” Williams had a slightly different take on the criminal justice issue. “If we change the culture of black America through parenting it would eliminate the justice system from being tilted the way it is,” he says. Politics is downstream of culture. Focus on the home and the politics will take care of itself.

When asked about the upcoming election, Brooks said that Joe Biden is popular “only because of one person: Obama…He gets the black card because [of] Obama.” Despite Biden’s success in the primaries with black voters, however, he thinks that he could lose the black vote the more that the incarceration issue is discussed on the campaign trail or at the debates. But don’t count on them pulling the lever for Republicans. While Brooks said that “I wish they would go out and vote for Trump and conservative values,” disenchantment with Biden over the crime issue is more likely to lead to them staying home, driving low voter turnout in black neighborhoods.

What about Kanye West? Perhaps the most influential black entertainer on the planet, and now, a Trump supporter. Brooks said, “I like Kayne,” specifically, “I appreciate his transformation. I like what he’s trying to do, that he’s being vocal about it. Speaking out about some of the ills of the music industry…I like that he’s talking about some conservative principles, especially as it relates to mass incarceration.” Are Brooks’s views about Kayne widespread in his local community? Not so fast. “They think Kanye is crazy, but [he] gets a pass because he’s a major entertainer, and he has great wealth.”

If someone with Kayne’s status and cultural capital is nevertheless written off for his rightward turn, Brooks and Williams face nearly insurmountable odds—at least as far as politics is concerned. Thankfully for their communities, and the country, their message is bigger than politics.

What does the Gospel mean to you? The answer that both men gave surprised me. Ask that question in other circles and you’re bound to get a lengthy explanation about different theories of the atonement. For them, the answer was simple: action. Pastor Brooks responded with enthusiasm: “Living it out in the flesh…It’s about loving God but it’s also about loving your neighbor. The Gospel has to be translated into action.” Similarly, Pastor Williams noted, “Seeing the need and then doing something to fulfill the need that you see.” Regardless of their politics, this is what makes their ministries so powerful. Both men possess seemingly boundless energy and unflinching courage. They’ve set out to change the world family by family and block by block. Their goal is to build a nationwide movement to provide resources for black communities to fight poverty by strengthening families, teaching job skills and entrepreneurship, and providing a place of refuge for those seeking to escape gang violence.

Conservatives like to retreat to seminars and conferences to debate ideology. While Brooks and Williams could no doubt hold their own in such a setting, they’ve taken a different path. Being men of action, they chose to spend their time building institutions that will continue to meet the spiritual, material, and intellectual needs of their communities long after they’re gone. Those in politics like to think in terms of election cycles, be it two years or four years. Brooks and Williams take the long view. What they’ve built will pay dividends for a century. In light of the ephemerality of our politics, we could learn from their example.